Introduction

Teacher questioning has been identified as a critical part of teachers’ work. The act of asking a good question is cognitively demanding, it requires considerable pedagogical content knowledge and it necessitates that teachers know their learners well. A number of research studies have shown that teachers rarely ask ‘higher order’ questions, even though these have been identified as important tools in developing student understanding (Hiebert & Wearne, 1993; Klinzing, Klinzing-Eurich, & Tisher, 1985). Research on the relationships between teacher questions and student learning has produced mixed results, both more generally (Klinzing et al., 1985) and in mathematics (Hiebert & Wearne, 1993). Hiebert and Wearne (1993) argue that questions need to be viewed from within the context of the kind of instruction that is taking place and in relation to the mathematical tasks. In a small comparative study of traditional and “alternative” elementary mathematics classrooms, they show that while teachers in “alternative” classrooms asked a high number of questions requiring recall, they also asked a larger range of questions, and asked more questions requiring explanation and analysis than did teachers in traditional classrooms.

The research that we report on in this paper focuses on teacher questioning in secondary mathematics classrooms. We draw from a larger, ongoing, longitudinal study that follows approximately 1000 students in three schools who experienced different teaching approaches. There are three different mathematics curricula across the three schools, two of which we might characterize as “reform” and one as “traditional”. In two of the schools, students choose between a reform and traditional curriculum. The reform curriculum takes an open-ended, applied mathematical approach in which students work predominantly on long projects that combine and integrate across areas of mathematics. The traditional approach comprises courses of algebra, then geometry, then advanced algebra - taught using traditional methods of demonstration and practice. In the third school, the teachers have created their own curriculum which fits into the traditional algebra-geometry-algebra divisions but which takes a more open, exploratory and conceptual approach to mathematics within these strands. We consider this to be a reform curriculum. In addition to monitoring the students over four years, we are studying one or more focus classes from each approach in each school. In these classes we observe and video lessons, and conduct in-depth interviews with the teacher and selected students. In our paper we will report on our analyses of classroom organization and teacher questions and how these relate to the different curricula, the mathematical tasks within the curricula, the mathematical direction that the lessons take and classroom environment. We will also discuss some methodological issues in analyzing questions.

Findings

One result of our study is the critical role played by the teacher in each approach. We found that crude labels such as ‘‘traditional’’ or ‘‘reform’’, while matching the curriculum approaches used, did little to distinguish effective and ineffective teaching. We thus undertook a closer analysis, both quantitative and qualitative, of the teaching environments. We began with a quantitative analysis of the main activities in each classroom. We classified all the time spent in each class as either being: Teacher Questioning; Teacher Talking; Groupwork; Individual Work; or Student Focus. The categories were mutually exclusive. We coded 6 lessons for each of 6 focus teachers in 30-second intervals and reached an inter-rater reliability of 85 percent. Our first finding that we will report in the paper is that classes taught by different teachers, using the same curriculum, generated very similar categorizations. The amount of teacher questioning and groupwork was higher among the reform curriculum teachers, and the amount of individual work and teacher talking was higher among the traditional teachers. But it was noticeable and significant that some teachers who used the same curriculum approach, but generated very different instructional environments, looked very similar on this broad categorization. Thus this broad categorization of time spent does not seem to capture teaching quality. In some ways this is unsurprising, most people know that teaching quality depends upon the detailed decisions teachers make, but many of the initiatives handed to schools by districts and governments stay at this broad level of detail, as teachers are told to lecture less, engage in group work or have student presentations. Our study reveals that teaching quality is enacted at a finer level of detail.

These results led us to undertake a second, more focused analysis – which involved looking explicitly at all the questions teachers asked, to the whole class and with individuals and groups. “Rich questions” (Wiliam, 1999) or questions that promote mathematical thinking (Watson & Mason, 1998) can come from existing curricula or resource materials for teachers. However the cognitive level of these questions/tasks is often lowered in subsequent interaction (Stein, Grover, & Henningsen, 1996; Stein, Smith, Henningsen, & Silver, 2000). On the other hand, standard mathematical tasks can be opened up for exploration with skilful teacher questioning (Lampert, 2001).

We developed nine categories of teacher questions, through a process of watching the teachers in our study and considering other analyses of questions, particularly those conducted by Hiebert and Wearne (199x) and Driscoll (1999),. Our first sets of videos were coded by different researchers and an inter-rater reliability exercise achieved 90 percent reliability. The remaining of lessons were then coded by Brodie. Table 1 shows the categories we used.

Table 1: Teacher Questions.

Question type Description Examples

1. Gathering information, checking for a method, leading students through a method Wants direct answer, usually wrong or right Rehearse known facts/procedures,Enable students to state facts/procedures[equivalent to closed, lower order questions] What is the value of x in this equation?How would you plot that point?

2. Inserting terminology Once ideas are under discussion, enables correct mathematical language to be used to talk about them What is this called in mathematics?How would we write this correctly mathematically?

3. Probing, getting students to explain their thinking Clarify student thinking Enable student to elaborate their thinking for their own benefit and for the class How did you get 10? Can you explain your idea?

4. Exploring mathematical meanings, relationships Point to underlying mathematical relationships and meanings. Make links between mathematical ideas Where is this x on the diagram? What does probability mean?

5. Linking & Applying Point to relationships among mathematical ideas and mathematics and other areas of study/life In what other situations could you apply this? Where else have we used this?

6. Extending thinking Extends the situation under discussion, where similar ideas may be used Would this work with other numbers?

7. Orienting / Focusing Helps students to focus on key elements or aspects of the situation in order to enable problem-solving What is the problem asking you? What is important about this?

8. Generating Discussion Enables other members of class to contribute, comment on ideas under discussion Is there another opinion about this?What did you say, Justin?

9. Establishing context Talks about issues outside of math in order to enable links to be made with mathematics at later point What is the lottery?How old do you have to be to play the lottery?

A second set of results that we will report are the patterns of questioning across the different approaches. We have found further clear distinctions between traditional and reform teachers. Our findings for the traditional teachers are stark – more than 95 percent of their questions are of type 1. In the case of the reform teachers, between 60 and 75 percent of their questions are of type 1. The teachers using reform approaches are more varied, with some of them asking mainly type 1) and 3) questions and others asking a significant number of type 4) questions, These differences are important in determining the direction and flow of lessons. In our paper we will provide a closer, qualitative analysis of these questions in action. This analysis will both show the importance of the particular questions teachers ask in establishing different instructional environments and the need for teacher learning opportunities that focus on teacher questioning.

We will conclude with some methodological reflections on the importance of capturing teacher differences, and the grain size of analysis that we have found helpful. We will also consider the implications of the questioning differences we recorded – for curriculum policy and for teacher learning.

References

Ainley, J. (1987). Telling questions. Mathematics Teaching(118), 24-26.

Driscoll, M. (1999). Fostering Algebraic Thinking. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hiebert, J., & Wearne, D. (1993). Instructional tasks, classroom discourse, and students' learning in second-grade arithmetic. American Educational Research Journal, 30(2), 393-425.

Klinzing, G., Klinzing-Eurich, G., & Tisher, R. P. (1985). Higher cognitive behaviours in classroom discourse: Congruencies between teachers' questions and pupils' responses. The Australian Journal of Education, 29(1), 63-75.

Lampert, M. (2001). Teaching problems and the problems of teaching. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Stein, M. K., Grover, B. W., & Henningsen, M. A. (1996). Building student capacity for mathematical thinking and reasoning: An analysis of mathematical tasks used in reform classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 33(2), 455-488.

Stein, M. K., Smith, M. S., Henningsen, M. A., & Silver, E. A. (2000). Implementing standards-based mathematics instruction: A casebook for professional development. New York: Teachers College Press.

Stubbs, M. (1976). 'Keeping in touch': Some functions of teacher talk. In M. Stubbs & S. Delamont (Eds.), Explorations in classroom observation. London: Wiley.

Watson, A., & Mason, J. (1998). Questions and prompts for mathematical thinking.

Wiliam, D. (1999). Formative assessment in mathematics, part 1: Rich questioning. Equals: Mathematics and special education needs, 5(2), 15-18.

with my Colleagues in the profession

after our pinning ceremony

About Me

- josephthedreamer

- EDUCATION: Any act or experience that has a formative effect on mind, character or physical ability of an individual. In its technical sense, Education is the process by which society deliberately transmit its accumulated knowledge, skills and values from one generation to another.

Friday, December 31, 2010

Thursday, December 23, 2010

TEACHER

Teacher

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

"Teachers" redirects here. For other uses, see Teachers (disambiguation).

For university teachers, see professor. For 'extra-help teachers', see tutor. For Parapros, see Paraprofessional educator.

| |

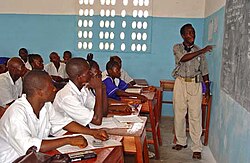

| Classroom at a secondary school in Pendembu, Sierra Leone. | |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Teacher, Educator, Lecturer |

| Type | Profession |

| Activity sectors | Education |

| Description | |

| Competencies | Teaching abilities, pleasant disposition, patience |

| Education required | Teaching certification |

| Fields of employment | Schools |

| Related jobs | Professor, academic, lecturer, tutor |

Informal learning may be assisted by a teacher occupying a transient or ongoing role, such as a parent or sibling or within a family, or by anyone with knowledge or skills in the wider community setting.

Religious and spiritual teachers, such as gurus, mullahs, rabbis pastors/youth pastors and lamas may teach religious texts such as the Quran, Torah or Bible.

Teaching may be carried out informally, within the family which is called home schooling (see Homeschooling) or the wider community. Formal teaching may be carried out by paid professionals. Such professionals enjoy a status in some societies on a par with physicians, lawyers, engineers, and accountants (Chartered or CPA).

A teacher's professional duties may extend beyond formal teaching. Outside of the classroom teachers may accompany students on field trips, supervise study halls, help with the organization of school functions, and serve as supervisors for extracurricular activities. In some education systems, teachers may have responsibility for student discipline.

Around the world teachers are often required to obtain specialized education, knowledge, codes of ethics and internal monitoring.

There are a variety of bodies designed to instill, preserve and update the knowledge and professional standing of teachers. Around the world many governments operate teacher's colleges, which are generally established to serve and protect the public interest through certifying, governing and enforcing the standards of practice for the teaching profession.

The functions of the teacher's colleges may include setting out clear standards of practice, providing for the ongoing education of teachers, investigating complaints involving members, conducting hearings into allegations of professional misconduct and taking appropriate disciplinary action and accrediting teacher education programs. In many situations teachers in publicly funded schools must be members in good standing with the college, and private schools may also require their teachers to be college peoples. In other areas these roles may belong to the State Board of Education, the Superintendent of Public Instruction, the State Education Agency or other governmental bodies. In still other areas Teaching Unions may be responsible for some or all of these duties.

Pedagogy and teaching

A primary school teacher in northern Laos.

The teacher-student-monument in Rostock, Germany, honours teachers.

GDR "village teacher" (a teacher teaching students of all age groups in one class) in 1951.

The objective is typically a course of study, lesson plan, or a practical skill. A teacher may follow standardized curricula as determined by the relevant authority. The teacher may interact with students of different ages, from infants to adults, students with different abilities and students with learning disabilities.

Teaching using pedagogy also involve assessing the educational levels of the students on particular skills. Understanding the pedagogy of the students in a classroom involves using differentiated instruction as well as supervision to meet the needs of all students in the classroom. Pedagogy can be thought of in two manners. First, teaching itself can be taught in many different ways, hence, using a pedagogy of teaching styles. Second, the pedagogy of the learners comes into play when a teacher assesses the pedagogic diversity of his/her students and differentiates for the individual students accordingly.

Perhaps the most significant difference between primary school and secondary school teaching is the relationship between teachers and children. In primary schools each class has a teacher who stays with them for most of the week and will teach them the whole curriculum. In secondary schools they will be taught by different subject specialists each session during the week and may have 10 or more different teachers. The relationship between children and their teachers tends to be closer in the primary school where they act as form tutor, specialist teacher and surrogate parent during the course of the day.

This is true throughout most of the United States as well. However, alternative approaches for primary education do exist. One of these, sometimes referred to as a "platoon" system, involves placing a group of students together in one class that moves from one specialist to another for every subject. The advantage here is that students learn from teachers who specialize in one subject and who tend to be more knowledgeable in that one area than a teacher who teaches many subjects. Students still derive a strong sense of security by staying with the same group of peers for all classes.

Co-teaching has also become a new trend amongst educational institutions. Co-teaching is defined as two or more teachers working harmoniously to fulfill the needs of every student in the classroom. Co-teaching focuses the student on learning by providing a social networking support that allows them to reach their full cognitive potential. Co-teachers work in sync with one another to create a climate of learning.

Rights to enforce school discipline

Main articles: School discipline and School punishment

Throughout the history of education the most common form of school discipline was corporal punishment. While a child was in school, a teacher was expected to act as a substitute parent, with all the normal forms of parental discipline open to them.In past times, corporal punishment (spanking or paddling or caning or strapping or birching the student in order to cause physical pain) was one of the most common forms of school discipline throughout much of the world. Most Western countries, and some others, have now banned it, but it remains lawful in the United States following a US Supreme Court decision in 1977 which held that paddling did not violate the US Constitution.[2]

30 US states have banned corporal punishment, the others (mostly in the South) have not. It is still used to a significant (though declining) degree in some public schools in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas. Private schools in these and most other states may also use it. Corporal punishment in American schools is administered to the seat of the student's trousers or skirt with a specially made wooden paddle. This often used to take place in the classroom or hallway, but nowadays the punishment is usually given privately in the principal's office.

Official corporal punishment, often by caning, remains commonplace in schools in some Asian, African and Caribbean countries. For details of individual countries see School corporal punishment.

Currently detention is one of the most common punishments in schools in the United States, the UK, Ireland, Singapore and other countries. It requires the pupil to remain in school at a given time in the school day (such as lunch, recess or after school); or even to attend school on a non-school day, e.g. "Saturday detention" held at some US schools. During detention, students normally have to sit in a classroom and do work, write lines or a punishment essay, or sit quietly.

A modern example of school discipline in North America and Western Europe relies upon the idea of an assertive teacher who is prepared to impose their will upon a class. Positive reinforcement is balanced with immediate and fair punishment for misbehavior and firm, clear boundaries define what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior. Teachers are expected to respect their students, and sarcasm and attempts to humiliate pupils are seen as falling outside of what constitutes reasonable discipline.[verification needed]

Whilst this is the consensus viewpoint amongst the majority of academics, some teachers and parents advocate a more assertive and confrontational style of discipline.[citation needed] Such individuals claim that many problems with modern schooling stem from the weakness in school discipline and if teachers exercised firm control over the classroom they would be able to teach more efficiently. This viewpoint is supported by the educational attainment of countries—in East Asia for instance—that combine strict discipline with high standards of education.[citation needed]

It's not clear, however that this stereotypical view reflects the reality of East Asian classrooms or that the educational goals in these countries are commensurable with those in Western countries. In Japan, for example, although average attainment on standardized tests may exceed those in Western countries, classroom discipline and behavior is highly problematic. Although, officially, schools have extremely rigid codes of behavior, in practice many teachers find the students unmanageable and do not enforce discipline at all.

Where school class sizes are typically 40 to 50 students, maintaining order in the classroom can divert the teacher from instruction, leaving little opportunity for concentration and focus on what is being taught. In response, teachers may concentrate their attention on motivated students, ignoring attention-seeking and disruptive students. The result of this is that motivated students, facing demanding university entrance examinations, receive disproportionate resources, while the rest of the students are allowed, perhaps expected to, fail.[unbalanced opinion] Given the emphasis on attainment of university places, administrators and governors may regard this policy as appropriate.

Obligation to honor students rights

Main article: Discipline in Sudbury Model Democratic Schools

Sudbury model democratic schools claim that popularly based authority can maintain order more effectively than dictatorial authority for governments and schools alike. They also claim that in these schools the preservation of public order is easier and more efficient than anywhere else. Primarily because rules and regulations are made by the community as a whole, thence the school atmosphere is one of persuasion and negotiation, rather than confrontation since there is no one to confront. Sudbury model democratic schools' experience shows that a school that has good, clear laws, fairly and democratically passed by the entire school community, and a good judicial system for enforcing these laws, is a school in which community discipline prevails, and in which an increasingly sophisticated concept of law and order develops, against other schools today, where rules are arbitrary, authority is absolute, punishment is capricious, and due process of law is unknown.[3][4]Teacher Enthusiasm

Since teachers can affect how students perceive the course materials, it has been found that teachers who showed enthusiasm towards the course materials and students can affect a positive learning experience towards the course materials. On teacher/course evaluations, it was found that teachers who have a positive disposition towards the course content tend to transfer their passion to receptive students.[5] Teachers cannot teach by rote but have to find new invigoration for the course materials on a daily basis. Teachers have to keep in mind that they are teaching new minds every term or semester.[6] Otherwise, teachers will fall into the trap of having done this material again and start feeling bored with the subject which in turn bore the students as well. Students who had enthusiastic teachers tend to rate them higher than teachers who didn’t show much enthusiasm for the course materials.[citation needed]Teachers that exhibit enthusiasm can lead to students who are more likely to be engaged, interested, energetic, and curious about learning the subject matter. Recent research has found a correlation between teacher enthusiasm and students’ intrinsic motivation to learn and vitality in the classroom.[7] Controlled, experimental studies exploring intrinsic motivation of college students has shown that nonverbal expressions of enthusiasm, such as demonstrative gesturing, dramatic movements which are varied, and emotional facial expressions, result in college students reporting higher levels of intrinsic motivation to learn.[citation needed] Students who experienced a very enthusiastic teacher were more likely to read lecture material outside of the classroom.

There are various mechanisms by which teacher enthusiasm may facilitate higher levels of intrinsic motivation. Teacher enthusiasm may contribute to a classroom atmosphere full of energy and enthusiasm which feed student interest and excitement in learning the subject matter.[citation needed] Enthusiastic teachers may also lead to students becoming more self-determined in their own learning process. The concept of mere exposure indicates that the teacher’s enthusiasm may contribute to the student’s expectations about intrinsic motivation in the context of learning. Also, enthusiasm may act as a “motivational embellishment”; increasing a student’s interest by the variety, novelty, and surprise of the enthusiastic teacher’s presentation of the material. Finally, the concept of emotional contagion, may also apply. Students may become more intrinsically motivated by catching onto the enthusiasm and energy of the teacher.[citation needed]

Research shows that student motivation and attitudes towards school are closely linked to student-teacher relationships. Enthusiastic teachers are particularly good at creating beneficial relations with their students. Their ability to create effective learning environments that foster student achievement depends on the kind of relationship they build with their students.[8][9][10][11] Useful teacher-to-student interactions are crucial in linking academic success with personal achievement.[12] Here, personal success is a student's internal goal of improving himself, whereas academic success includes the goals he receives from his superior. A teacher must guide his student in aligning his personal goals with his academic goals. Students who receive this positive influence show stronger self-confidence and greater personal and academic success than those without these teacher interactions.[11][13][14]

Students are likely to build stronger relations with teachers who are friendly and supportive and will show more interest in courses taught by these teachers.[12][13] Teachers that spend more time interacting and working directly with students are perceived as supportive and effective teachers. Effective teachers have been shown to invite student participation and decision making, allow humor into their classroom, and demonstrate a willingness to play.[9]

The way a teacher promotes the course they are teaching, the more the student will get out of the subject matter. The three most important aspects of teacher enthusiasm are enthusiam about teaching, enthusiasm about the students, and enthusiasm about the subject matter. A teacher must enjoy teaching. If they do not enjoy what they are doing, the students will be able to tell. They also must enjoy being around their students. A teacher who cares for their students is going to help that individual succeed in their life in the future. The teacher also needs to be enthusiatic about the subject matter they are teaching. For example, a teacher talking about chemsitry needs to enjoy the art of chemistry and show that to their students. A spark in the teacher may create a spark of excitement in the student as well. A enthusiatic teacher has the ability to be very influential in the young students life.

Misconduct

See also: Child abuse

Misconduct by teachers, especially sexual misconduct, has been getting increased scrutiny from the media and the courts.[15] A study by the American Association of University Women reported that 0.6% of students in the United States claim to have received unwanted sexual attention from an adult associated with education; be they a volunteer, bus driver, teacher, administrator or other adult; sometime during their educational career.[16]A study in England showed a 0.3% prevalence of sexual abuse by any professional, a group that included priests, religious leaders, and case workers as well as teachers.[17] It is important to note, however, that the British study referenced above is the only one of its kind and consisted of "a random ... probability sample of 2,869 young people between the ages of 18 and 24 in a computer-assisted study" and that the questions referred to "sexual abuse with a professional," not necessarily a teacher. It is therefore logical to conclude that information on the percentage of abuses by teachers in the United Kingdom is not explicitly available and therefore not necessarily reliable. The AAUW study, however, posed questions about fourteen types of sexual harassment and various degrees of frequency and included only abuses by teachers. "The sample was drawn from a list of 80,000 schools to create a stratified two-stage sample design of 2,065 8th to 11th grade students"Its reliability was gauged at 95% with a 4% margin of error.

In the United States especially, several high-profile cases such as Debra LaFave, Pamela Rogers, and Mary Kay Latourneau have caused increased scrutiny on teacher misconduct.

Chris Keates, the general secretary of National Association of Schoolmasters Union of Women Teachers, said that teachers who have sex with pupils over the age of consent should not be placed on the sex offenders register and that prosecution for statutory rape "is a real anomaly in the law that we are concerned about." This has led to outrage from child protection and parental rights groups.[18]

Teaching around the world

There are many similarities and differences among teachers around the world. In almost all countries teachers are educated in a university or college. Governments may require certification by a recognized body before they can teach in a school. In many countries, elementary school education certificate is earned after completion of high school. The high school student follows an education specialty track, obtain the prerequisite "student-teaching" time, and receive a special diploma to begin teaching after graduation.International schools generally follow an English-speaking, Western curriculum and are aimed at expatriate communities.[

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)